Brain Images Show Effects of Celiac Disease

By Van Waffle

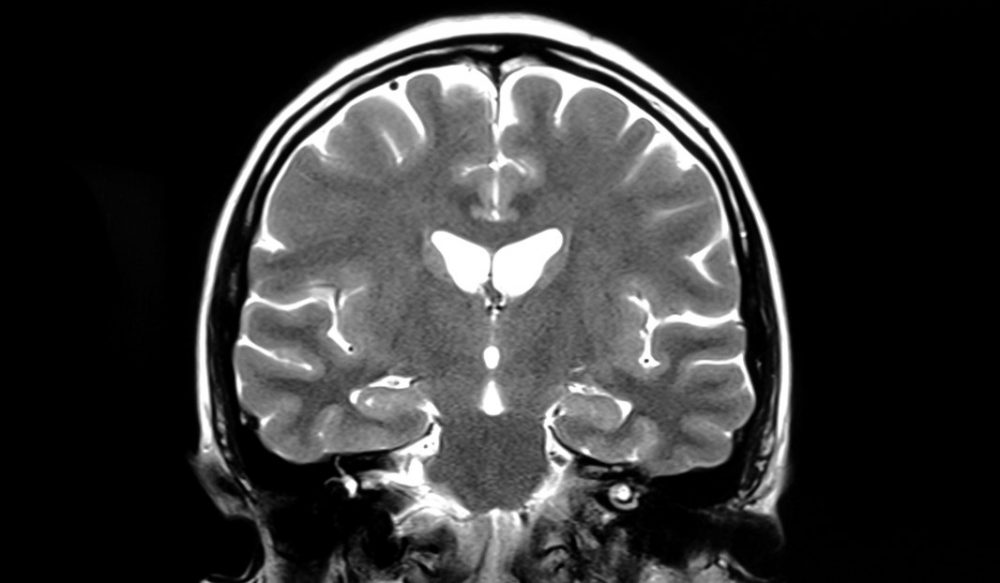

A recent study from the United Kingdom found changes in the brains of celiac patients, linking them with mental health problems. While it was previously not known how celiac disease could impair cognitive function, this research used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to find injuries to brain tissue. A group of adult celiac patients showed neurological problems in three ways: worsened mental health, impaired brain function, and damage to cerebral tissue.

“These patients tend to have headaches that respond to a gluten-free diet." - Nigel Hoggard, MD, Professor of Neuroradiology at University of Sheffield, Royal Hallamshire Hospital

Nigel Hoggard, MD, Professor of Neuroradiology at University of Sheffield, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, says he became interested in the relationship between celiac disease and brain health after over a decade of performing brain imagery for celiac patients. It was clear that some patients had “excessive signal changes in their cerebral white matter,” he says. “These patients tend to have headaches that respond to a gluten-free diet, which has been dubbed gluten encephalopathy. We have already undertaken a prospective study in patients with newly diagnosed celiac disease which showed some changes were already present even at that initial stage.”

An opportunity to study these effects in the national population arose when UK Biobank recruited 500,000 people, ages 40 to 69, to provide experimental medical data. In 2019, cognitive test and brain scan results became available from 28,787 participants. From this set, Hoggard’s team identified 104 celiac patients with a mean age of 63 and compared them with 198 people who did not have celiac disease, but had similar age, sex, education level, body mass index and hypertension.

On cognitive tests, celiac patients showed slower reaction time. There were higher indications of poor mental health including anxiety, depression, thoughts of self-harm and health-related unhappiness. Brain scans showed increased damage to cerebral white matter similar to effects of aging.

Magnetic resonance, used in this study, detects how quickly and in what direction water diffuses around nerve fibers in the brain. It found indications of damage to white matter. This may result from damage to nerves themselves as in multiple sclerosis or from small vessel disease involving poor blood supply often seen in aging patients.

Hoggard says he was surprised to identify detectable changes in a group of this age: “I wasn’t expecting any impact that we could measure until we specifically started looking at more elderly patients who may have had decades of gluten sensitivity.”

Shayna Coburn, Ph.D., psychologist in the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at Children’s National Hospital, who did not work on this research, says, “This study is strong because of its design to compare the people with celiac disease with people without celiac disease and its cutting edge approach to look at their brains using MRI technology.”

However, she points to some limitations. Although brain changes and cognitive problems were both significant in the celiac group, they were not necessarily associated; patients with brain changes did not necessarily perform poorly on tests. A lack of statistical significance may result from the small study group.

“This is an important lesson that is widely known in research on the brain: just because it might look different does not always mean it causes problems,” Coburn says in calling for further study.

Other limitations include no information on how long patients were gluten-free, the limited age group and lack of clarity on how mental health was assessed, Coburn says.

“Based on this study alone, doctors should not necessarily expect brain damage in their patients with celiac disease. Still, perhaps this study will help doctors take celiac disease more seriously as a condition that affects more than the digestive system. Specifically, it raises awareness that there could be neurological and emotional challenges in some (but not all) people with celiac disease,” Coburn says, adding that doctors should screen celiac patients for these health concerns and refer them to a specialist if needed.

The study emphasizes that neurological damage in celiac patients is driven by exposure to gluten.

The study emphasizes that neurological damage in celiac patients is driven by exposure to gluten. How the damage occurs remains unknown. Celiac disease involves inflammation and any kind of inflammation is known to increase the risk for mood disorders, says Hoggard. However, ongoing research at Sheffield implicates an antibody for transglutaminase 6 that appears in people with gluten sensitivity. The antibody is associated with balance problems involving the brain in some celiac patients.

“However the target for these antibodies is found in other areas of the brain, so whether there is any direct effect of these antibodies on mood or cognition isn’t known at the current time,” says Hoggard, “but we are doing some research into this right now.”

Strict gluten avoidance is important for brain health in celiac patients.

“All of the evidence that we have from patients with neurological problems caused by gluten sensitivity is that they are halted by adhering to a strict gluten-free diet,” says Hoggard, “but the need for strict adherence in our experience is perhaps even more important for neurological problems than it is for bowel-related symptoms.”

For more information the study was published in Gastroenterology: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0016508520302390