Pilot Study Connects Celiac Disease With Pollutants

By Van Waffle

A small pilot study suggests, but does not prove, that chemical pollutants might be an environmental factor associated with celiac disease in children. This is the first research to link the autoimmune disorder with persistent organic pollutants (POPs) detected in blood samples from celiac patients. POPs are synthetic chemicals that persist for many years in the environment.

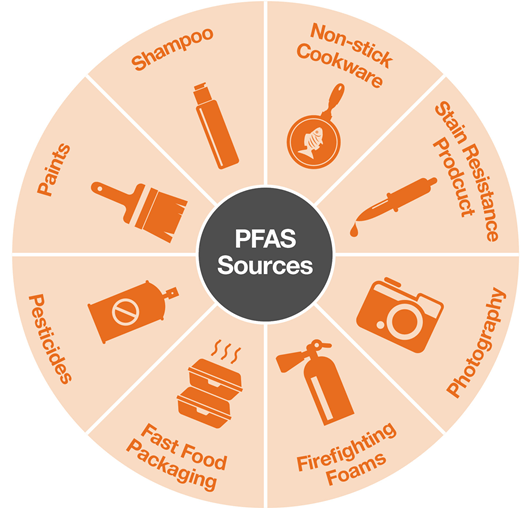

According to the study, published in the journal Environmental Research, higher blood concentrations of dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) doubled the risk of celiac disease. When stratified by gender, the effect was much higher in females. DDE is a persistent remnant of DDT, an insecticide banned in the 1970s. The results also showed an increased risk for celiac disease in females from perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and in males from polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs). PFAS have been used in non-stick, cleaning and other products. PBDEs are fire retardants that readily leach out of carpets and other materials.

“We were surprised at the results – that we did see some statistical significance – which leads us to think that more could be done here, but this was truly a very preliminary study,” says Abigail Gaylord, graduate student, Department of Population Health, and assistant to the study’s lead researcher, Jeremiah Levine, MD, Department of Pediatrics, NYU School of Medicine.

“We weren’t expecting to do the gender-specific analysis because there weren’t a ton of study subjects. It’s hard as you break it down further and further to get valid results, but we were really interested in what we saw,” says Gaylord, who did background research for the study and conducted statistical analysis on the results.

The data came from 88 patients aged 21 years or less at New York University Langone’s Hassenfeld Children’s Hospital. All were being assessed for gastrointestinal troubles. Based on abnormal blood tests and biopsy, 30 were diagnosed with celiac disease, while 58 who did not have celiac disease were recruited for comparison.

“This joins a growing body of studies that propose environmental risk factors for celiac disease. There is certainly good reason to hunt for such risk factors, given the rise in celiac disease in recent decades. That said, one should interpret the findings here with caution.

Celiac disease is hereditary. Almost all people with celiac have either the HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 gene, which can be determined by blood tests. Although not every child in the study had a high genetic risk for celiac disease, data analysis accounted for this, says Gaylord: “Basically there’s an eight level scale, with eight being highest risk based on your genotype and one being the lowest risk. We included that in our statistical analysis and that is how we controlled for the genetic factor.”

Benjamin Lebwohl, MD, Director of Clinical Research at the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University, New York, who is not involved with this research, says “This joins a growing body of studies that propose environmental risk factors for celiac disease. There is certainly good reason to hunt for such risk factors, given the rise in celiac disease in recent decades. That said, one should interpret the findings here with caution. The authors found an association with persistent organic pollutants, but it is not clear if those elevated levels have anything to do with causing celiac disease but rather may reflect other unrelated differences between the celiac subjects and the control population. Moreover, the range of magnitude of the identified association is wide, reflecting the small sample size of the study.”

Lebwohl adds, “Further, this study only examined children with diagnosed celiac disease—given that many celiac patients are undiagnosed, children who get diagnosed are likely different in important ways related to health care utilization and socioeconomics, which may be associated with these pollutant levels. So there are a number of limitations that prevent us from drawing sweeping conclusions, but such a study does raise this as a possibility and mandates follow-up work, ideally with a larger group followed forward in time.”

Gaylord says further study would require a larger sample size for more robust data. She also suggests measurement of factors affecting how the body absorbs chemicals.

“We use so many new synthetic chemicals now in everyday products, so we’re very much exposed to them,” she says. “The increase in the use of these synthetic chemicals as well as celiac disease pointed towards something that could possibly be a correlation. Correlation is going to be present in a lot of things, but it’s definitely worth looking into.”

SOURCE: https://bit.ly/2WI50Ow Environmental Research, online May 11, 2020.