A Gluten-Digesting Enzyme Passes Phase 1 Trial

By Van Waffle

TAK-062, an orally administered synthetic enzyme that survives the acidity of the stomach and digests gluten effectively, has passed its phase 1 clinical drug trial, indicating it is safe to use in celiac patients. Meanwhile, a small, preliminary phase 2 trial in people without celiac disease showed it successfully breaks down at least 95 percent of gluten while passing through the stomach. It is hoped that this drug could treat celiac patients who continue to have poor outcomes despite their best efforts to avoid gluten. The prototype for the drug was developed by a team of undergraduate students and won an engineering competition.

As part of its efforts to accelerate research into treatments for celiac disease, the Celiac Disease Foundation recruited celiac disease patients for the phase 1 clinical trial.

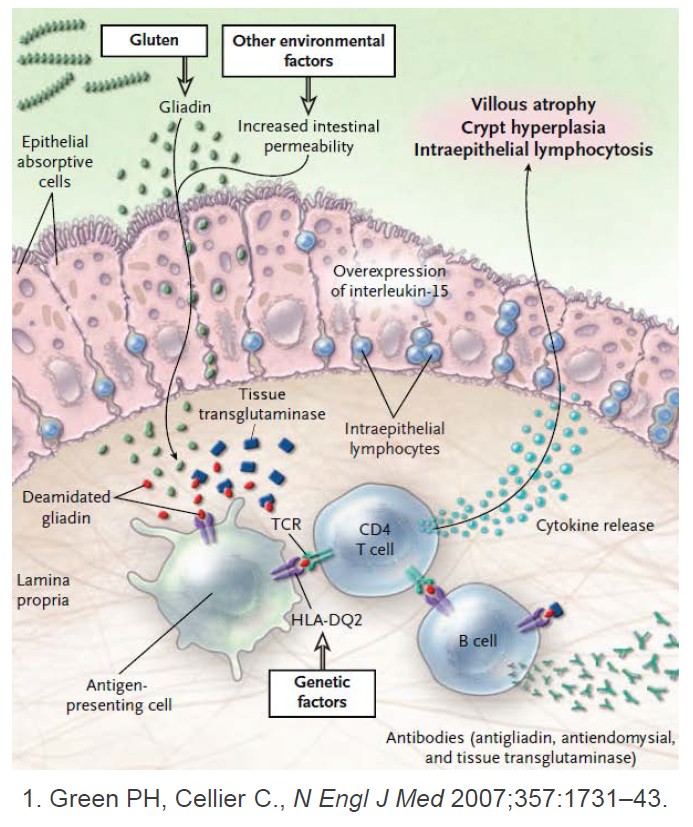

Enzymes are proteins that convert other molecules from one form to another, including digesting food into smaller, more usable particles. Microbes living in the gut help produce digestive enzymes. In humans, these naturally occurring enzymes have difficulty breaking down gluten, but this isn’t typically a problem, unless you have celiac disease. The goal of finding or developing an enzyme to break down gluten before it reaches the small intestine and damages the lining is not new, however, earlier candidates failed to do the job.

A principal reason other enzyme candidates have failed is that the treatment needs to work quickly, effectively and specifically for gluten, says Daniel Leffler, MD, a gastroenterologist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Medical Officer of Takeda Pharmaceuticals in Boston who worked on the TAK-062 phase 1 trial. First, a successful enzyme treatment for gluten must survive the stomach’s high acidity. Second, most enzymes are not very fussy about what proteins they latch onto so a full meal dilutes their effectiveness leaving too much gluten behind.

“The more focused your enzyme is, the better job it can do at degrading the thing you want it to degrade. You don’t want your enzyme to multitask,” explains Leffler. Based on recent clinical trials, TAK-062 looks more promising.

“We went to a local fast food place and got a hamburger and milkshake, brought it back, and looked at the ability to break down gluten in the bun,” she says. “The enzyme is very powerful even in the presence of these other proteins.”

The treatment was invented by undergraduate students from University of Washington, Seattle. Ingrid Pultz, PhD was the graduate student advisor for the team that participated in the annual International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition (iGEM). She says some of the students wanted to work on a celiac disease drug because they had friends with the disease.

“We started with an enzyme that didn’t have much activity against the immunogenic regions of gluten, but it worked very, very well in stomach conditions,” says Pultz. “We then used the tools of computational protein design to re-engineer the part of the enzyme that breaks down its natural substrate, and changed that by flopping some amino acids with other naturally-occurring amino acids. We designed an enzyme that was predicted to break down gluten instead.”

Their prototype won the 2011 iGEM championship, the first time a US team won the award. Pultz continued studying the enzyme as her postdoctoral project. Then, over the next few years, she developed it at the newly formed Institute for Protein Design in Seattle. Pultz is now Chief Scientific Officer and co-founder of PvP Biologics based in San Diego, California, which conducted the phase 1 trial.

“We went to a local fast food place and got a hamburger and milkshake, brought it back, and looked at the ability to break down gluten in the bun,” she says. “The enzyme is very powerful even in the presence of these other proteins.”

“Not in a test tube anymore,” says Leffler. “This was basically a smoothie with some ice cream, some whole wheat bread, some orange juice, all blended up together to simulate something that was sort of like a real meal.”

A small tube passing through the nose into the volunteers’ stomachs allowed researchers to observe the enzyme’s effect. Across varying doses the test showed, “really robust gluten digestion, on average around 98 percent,” says Leffler.

In volunteers who consumed the amount of gluten contained in one or two slices of bread, treatment reduced gluten in the stomach within 35 minutes, “to well below 50 milligrams,” achieving less than the amount considered toxic to people with celiac disease, says Leffler.

In volunteers who consumed the amount of gluten contained in one or two slices of bread, treatment reduced gluten in the stomach within 35 minutes, “to well below 50 milligrams,” achieving less than the amount considered toxic to people with celiac disease, says Leffler.

“Starting later this year would be a large phase 2 trial in people with celiac disease who have not fully responded to the gluten-free diet, so they have ongoing symptoms and ongoing intestinal damage,” says Leffler. “And we will be putting them on this TAK-062 or a placebo and seeing if it can help relieve symptoms and improve intestinal healing,” while they continue a gluten-free diet.

PvP received funding from Takeda to conduct the phase 1 study. Takeda has now acquired PvPs to proceed with clinical trials.

If phase 2 trials find the drug effective in the target patients, and at what dosage, it would enter phase 3 to confirm safety and efficacy in a larger population before being eligible for US Food and Drug Administration approval.