Teen Transitions, Probiotics, and FODMAPs in Spotlight at Columbia Celiac Symposium

By Van Waffle

The Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University Biennial Symposium squeaked ahead of the COVID-19 outbreak in New York. Most speakers from around the world were able to attend on March 6 and 7, though a few had to appear by remote video due to flight restrictions. A last-minute decision to live-stream the symposium allowed registrants to view it from the safety of home. Discussion panels fielded questions sent by text and from the reduced live audience.

Marilyn Geller, Chief Executive Officer of the Celiac Disease Foundation, says, “Celiac disease is the most prevalent autoimmune disorder without a single, FDA-approved therapeutic. This is largely because our federal government has refused to take this devastating disease seriously. For 30 years, the Celiac Disease Foundation has used peer-reviewed research as the core of our efforts to push our federal government to act responsibly. Our sponsorship of The Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University’s Biennial Symposium, which brings together the world’s greatest researchers to share these findings and collaborate on future projects, continues that work.”

Following are a few highlights.

Teens Taking Responsibility

The passage from teenager to adulthood is almost always challenging, but even more so for celiac patients. Dascha Weir, MD, Boston Children’s Hospital, said young adults need support moving from parental care to managing their own health. A child normally begins developing self-management skills from age 12—such as asking how food was prepared—and transitions to autonomy at 16. She stressed the importance of allowing children to take more responsibility during this period.

Celiac patients need lifelong follow-up to ensure they adhere to a gluten-free diet and to monitor related health risks. Research shows that only half of celiac patients believe they need ongoing care with a specialist. One-quarter stop attending follow-up visits within a year after diagnosis.

Weir says the teen years are a period of high risk for patients to drop out of follow-up with a celiac disease specialist. Children whose gluten-free diet was closely managed by their parents may have a false sense of security about their lack of symptoms. One study found patients diagnosed at age 13 or older were more likely to transition successfully to an adult health care provider because they are more aware of the consequences of eating gluten. A pediatrician’s referral can also assist transition to an adult health care provider. She recommended development of a “celiac passport,” such as a phone app, to summarize a patient’s celiac history to assist future good care.

An expert in the audience responded that a passport is already being used in Europe: “It’s boring to fill out but patients like it.”

Bacteria to Treat Celiac Disease

Probiotics could potentially treat celiac disease, but none are recommended and the science isn’t close to offering guidance. Better understanding of the potential of probiotics to treat celiac disease requires more coordination among researchers, according to Elena Verdú, MD, professor of gastroenterology at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Various bacteria appear to play a role in the celiac disease gut microbiome. Some cause inflammation, some are beneficial, and some were previously unknown to science. Research must start to move from identifying microbial species to understanding how they affect the gut, Verdú said. A recent review of existing research could not draw overall conclusions about how microbes affect patient symptoms because the studies failed to report comparable data. She called for researchers to standardize how they record symptoms.

Verdú described elafin, a human anti-inflammatory protein discovered at McMaster University. Its production is reduced in people with celiac disease. Restoring it could block damage to the gut lining. Although microbes can be engineered to produce elafin, regulations would not allow these genetically-modified organisms in clinical trials for humans. Further research has found a natural microbial alternative that produces a protein similar to elafin. It appears equally effective in preventing gluten damage in mice. However, studies are needed to demonstrate its effect in humans.

Cost-Benefit of Low-FODMAPs Diet

A low-FODMAPs diet is increasingly being used to treat symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome that may occur in celiac disease patients. Peter Gibson, a professor of gastroenterology at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, reported ongoing research to explore possible down-sides of this elimination diet.

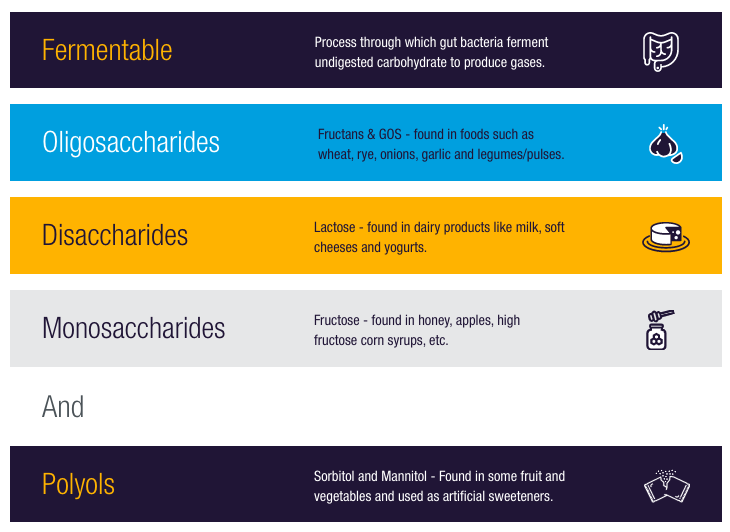

FODMAPs include a variety of carbohydrates that are difficult to digest: fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols. They occur in many plant-based foods and can cause uncomfortable fermentation in the lower digestive tract. Temporarily restricting foods that contain FODMAPs from the diet under a dietitian’s advice can restore a healthier microbiome. Then FODMAPs can be progressively reintroduced.

Drawbacks of a low-FODMAP diet include:

- It is poor in certain nutrients such as fiber.

- It increases risk for eating disorders.

- It reduces levels of beneficial Bifidobacteria, and the health impact of this effect is unknown.

However, the timeline for a low-FODMAP diet is relatively short. Gibson argued that fiber intake improves when patients reintroduce foods. Levels of Bifidobacteria also need to be brought back up. More research is needed to clarify effects of using the diet alongside a gluten-free diet in celiac disease patients.